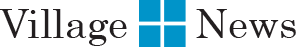

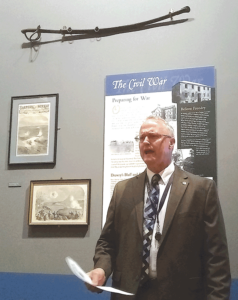

ABOVE: Russ Lescault speaks at the Chesterfield County Museum, 6831 Mimms Loop; A black-powder pistol made in Spain is similar to models that could have been used in a duel.

Russ Lescault loves talking about history.

Lescault, 61, is a retired hostage negotiator and search and rescue coordinator. He was also the resident historian for the Chesterfield police department and sheriff’s office and a part-time faculty member at Virginia State and Virginia Commonwealth universities.

Last week, he gave a presentation titled, “Early Heroes and Villains of Chesterfield County.”

Speaking at the county museum Oct. 11, Lescault regaled the small crowd with stories about Chesterfield’s history.

Preaching a crime

Among these stories was that of John Weatherford, a Baptist minister who was locked up for five months for preaching without a license or consent of the Anglican Church in 1773. Despite this, crowds would gather outside the jail to hear Weatherford preach, Lescault said.

In response, John Archibald ordered that a fence be built in front of the jail, Lescault said, adding that visitors would raise bandanas into the air to let Weatherford know they were ready to hear him preach.

The jail officials built bonfires underneath his window so that the smoke would choke him during a sermon.

Also of note was Virginia law at the time, which included a fine of five shillings, 50 pounds of tobacco or 10 lashes for not attending church at least once a month.

In response, Thomas Jefferson wrote a state religious freedom statute that passed in 1786. Jefferson was so proud of this law that he instructed that his tombstone note that he was its author, along with the Declaration of Independence and that he was the father of the University of Virginia.

Dueling newspapermen

Lescault told about a duel between John Hampton Pleasants and Thomas Ritchie Jr. that resulted in Pleasants’ death. Pleasants founded the Richmond Whig, and Ritchie was with the Richmond Enquirer. In 1846, Ritchie wrote an editorial attacking Pleasants’ anti-slavery stance and implying that he was a coward. Pleasants then challenged Ritchie to a duel, although the state had outlawed the practice in 1810.

Pleasants and Ritchie came to the duel armed to the teeth. Pleasants bore a sword cane, two black-powder pistols, a revolver and a Bowie knife, while Ritchie had a Roman sword and seven pistols. Pleasants shot once into the air, and Ritchie responded by shooting him five times. In his last moments, Pleasants asked that Ritchie not be prosecuted. He was, but a jury found him not guilty. However, Ritchie left Pleasants’ daughter $25,000 when Ritchie died two years later.

Robiou’s death

In 1851, Anthony Robiou was found shot dead outside the gates of his Bellgrade Plantation, which Lescualt noted is where Ruth’s Chris Steak House is today. This came after Robiou evicted his wife, Emily, after a few years of marriage and began a public campaign speaking ill of her virtue. Emily’s father, John Wormley, was charged with murder, and his two trials lasted two years. The first trial resulted in a guilty verdict, but was overturned because sheriff’s deputy George Snelling served alcohol to the jury before their deliberations. The second trial also resulted in a conviction, and Wormley was hanged. Some 4,000 people – one-quarter of the population of Chesterfield at the time – attended a 90-minute religious service that preceded the execution. Wormley, a local lawyer, spoke for 15 minutes prior to his execution. He confessed to the crime, asked for forgiveness and attempted to clear his daughter’s reputation. Shortly thereafter, Emily Robiou married the man with whom Robiou accused her of committing adultery: John Reid, a man she had loved before marrying Robiou. Anthony and Emily Robiou’s child was killed by an unknown assailant during the trials, Lescault said. The child was presumed to be Anthony’s since he came to visit him after Emily’s eviction.

Beatties, bearded man, Binford

In 1911, Louise Beattie was shot and killed. Her husband, Henry Beattie, who was the son of a prominent Richmond family, was charged with murder. The story made headlines across the country. Henry Beattie was charged with shooting his wife while they were sitting in a Ford Model A on Midlothian turnpike. He claimed that a bearded man shot his wife. Police used search dogs, but they never found the scent of the alleged assailant or an escape route.

Beattie said the bearded drunk man stepped in front of their car, forcing him to brake. Beattie said he leaped out of the car, tangled with the attacker, pulled his gun away, and threw it in his vehicle. The bearded man fled, and Beattie took off driving, but a bump in the road resulted in the gun exiting the vehicle, Beattie said. The gun was found 25 feet from the road. Beattie told a detective that the bearded man shot Louise from six feet away, but she did not have any powder burns on her face. Beattie’s cousin, Paul Beattie, told authorities that he delivered a shotgun to Henry a few days before the murder. It was revealed that Beattie was living a double life and had a 13-year-old mistress, Beulah Binford, who was living in an apartment furnished and paid for by Beattie.

The media attention was so large that a special telegraph station was set up and special deputies were housed in tents outside the jail and courthouse during the two-week trial. Beattie ended up confessing and was convicted and hanged. A song about the murder was written and recorded by country singer Kelly Harrel in 1927, Lescault said.

Editor’s note: Lescault is willing to speak to audiences about Chesterfield history. If interested, email [email protected].