It’s one of the most peaceful times of the year in the little village of Chester, with spring in the air and more warm weather than cold. Usually, there are casual conversations on porches and in front of businesses in the center of the village. But not this year. It’s 1864, and we are at war, a civil war that is tearing the nation apart, and a fierce battle is raging outside of the village.

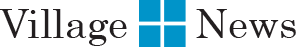

As the Union forces tried to take more ground, troops battled around what the community called the Winfree house at the time. Years after the war, it became known by the color it was painted: the Yellow House.

The woman who lived there approached Col. William Fowler of the Union troops with a fierce glare in her eyes, walked to the fence along the road, and, in a tone of voice indicating she was both angry and excited, ordered him to take the guns away and told him to leave. The sound and blasts from the cannon were breaking the glass panes in the windows of her home. Bullets flew about. He suggested that she go to her cellar for safety. She persistently refused and was highly upset. All his pleas would not move her from his cannons. This spunky woman told Fowler to leave and take his cannon with him. Even the Confederates couldn’t do that. And only after the Union ran out of ammunition did they leave.

Today, the “Yellow House” is much the as it was in May of 1864 although painted white. The huge tract that once surrounded it is much smaller, now flanked by Sunset Memorial Park, the YMCA, and developments that have sprouted like mushrooms after a rain. But the house is still quite intact, with a few modifications. It once served as a school for young southern girls who left their initials scratched in the windowpanes, all adding to its rich history. Even the bees once made their home in a bullet hole in the side of the house.

In the Battle for Chester Station, the Winfree house stood a short distance from the road into Chester, and throughout the battle it sustained damage from the Confederates, especially around the chimney with quite a few bullet holes. The intent was to dislodge the Union sharpshooters. Confederates tried twice to break the Union line. The 9th and 38th Virginia Infantries charged down the turnpike (Jefferson Davis Highway), and part of the 169th New York Infantry gave way, abandoning that portion of the line and one cannon. The 14th, 53rd, and 57th Virginia Infantries converged from three directions to make the second assault on the Federals around the Winfree house.

As the defenders’ ammunition dwindled, desperately needed Union infantry and artillery enforcements arrived just in time, deploying directly into the Winfree House lane and along the turnpike, checking the Virginians’ advance. Outnumbered, the beleaguered Southerners began to give ground. Adding to the confusion, Federal artillery shells ignited the woods early in the action, and the smoke and flames driving into the Confederate lines and deranged the precision of movements. Both sides fought gallantly and fiercely, including in hand-to-hand combat. The Federals soon retired to their Bermuda Hundred lines.

Two Confederate brigades had faced an Ohio regiment, which was pushed back despite arrival of reinforcements from Hawley’s brigade that arrived on the field. The growing Union reinforcements started to outnumber them, and the Confederates were compelled to retire to Drewry’s Bluff, while at the same time the Federals withdrew east to Bermuda Hundred. The result was a draw, with neither side having surrendered, being defeated, or gaining any ground. The Union forces succeeded in destroying some railroad track, and the Confederate forces succeeded in stopping them from doing any more damage. In the drawing, the 1st Connecticut Light Battery is posted near the Winfree house to repulse Confederate forces.

Confederate attacks in May 1864 failed to dislodge Union infantry stationed along the Southern communication and supply line lines from Richmond to Petersburg. Although Union forces held the battlefield, they soon withdrew to Bermuda Hundred and were “bottled up” there. The action at Chester Station was a relatively minor battle of the Bermuda Hundred Campaign, and it ended indecisively.

The Winfree house was saved and soon repaired. Around 1880, a Mr. Whiteside from Pennsylvania who had fought for the Union side in this area during the war, came to Chester and settled on this 300-acre farm, paying just $2,500. He left the place to his daughters, and the land was subsequently divided. P.W. Wing bought it in 1906 and put plumbing in the house. Supposedly this house had the first bathroom in Chester., you can just barely see the house from West Hundred road.